This week for Black History Month, MetroConnects honors a Greenville native whose music, acting and activism richly deserve a place in Greenville’s history. Born in 1914, Joshua Daniel White broke barriers throughout his career, appearing on stage in integrated acts and performing for the White House, all in a pre-Civil Rights era in which he was often barred from patronizing the very venues he played in.

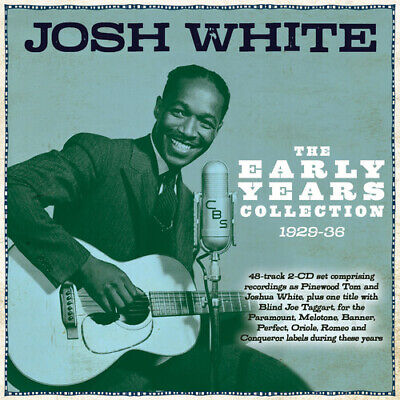

The Early Years

In recent years, Josh White has begun to gain the recognition he so richly deserves. Not only was the blues and folk musician famous for his tunes, but he was also an early civil rights activist who performed protest songs and sang at human rights rallies. White’s childhood experiences no doubt contributed to his career as an activist musician. His early years were shaped by church and family — his father was a local tailor and minister in Greenville, and his mother played the autoharp. White sang in church and was reading the bible by the time he was five. But in 1921, tragedy struck. A white bill collector came to White’s home and spit on the family’s floor. White’s father was enraged and shoved the white man out the door. Later that night, White’s father was arrested, beaten and dragged through town from a rope tied to a horse. The physical and mental damage was irrevocable. He spent the rest of his life in a mental institution, where he died in 1930.

A Traveling Act

Left alone to care for five children, life was hard for White’s mother. White was already a talented musician by the age of nine, and so he left home to join John Henry “Big Man,” a blind traveling musician. Arnold agreed to send White’s mother $4 a week for his services, and had him sing and dance in the streets, often “renting” him out to other showman.

By 14, White had learned to play guitar and was ready to make his first recordings. He traveled to Chicago with “Blind Joe” Taggart,” who White said was “tricky, nasty, and mean” (from Blues: A Regional Experience by Bob L. Eagle and Eric S. LeBlanc). The recording executives recognized his talent and removed him from the exploitative traveling musicians. He lived for a time with J. Mayo Williams, who worked for Paramount, attended school and made numerous recordings as a sideman.

His Big Break

In 1932, when White was 18 years old, he returned home to Greenville due to a leg injury. It was here that he began his own recording career with the New York-based American Record Company. His mother agreed to allow him to record his religious repertoire there in Greenville, but she disagreed with his secular blues singing. He ended up heading to New York where he had more freedom to record songs of his choosing. He released these “race albums,” as they were called, under the names Josh White and Pinewood Tom.

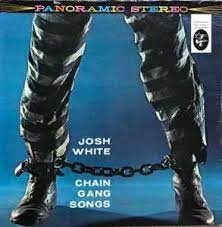

By 1935, his music began to shift, indicating his burgeoning political consciousness. He included songs written by the activist Bob Miller, including “Silicosis Blues,” a lament for the workers involved in the “Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster,” and “No More Ball and Chain,” a song that protested working conditions of Black laborers. Not long after, he discovered his aptitude for the stage and played Blind Lemon Jefferson in the musical John Henry, alongside Paul Robeson, who played the title character. Together, White and Robeson convinced the writers of the musical to remove the “N-word” from the script and replace it with the word “man.” A few years later, White recorded Chain Gang with the band he then led — Josh White and the Carolinians. The social commentary of the album was so controversial that Columbia Records’ John Hammond had to fight to get it produced.

By 1935, his music began to shift, indicating his burgeoning political consciousness. He included songs written by the activist Bob Miller, including “Silicosis Blues,” a lament for the workers involved in the “Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster,” and “No More Ball and Chain,” a song that protested working conditions of Black laborers. Not long after, he discovered his aptitude for the stage and played Blind Lemon Jefferson in the musical John Henry, alongside Paul Robeson, who played the title character. Together, White and Robeson convinced the writers of the musical to remove the “N-word” from the script and replace it with the word “man.” A few years later, White recorded Chain Gang with the band he then led — Josh White and the Carolinians. The social commentary of the album was so controversial that Columbia Records’ John Hammond had to fight to get it produced.

With Hammond’s support, White put together a series of appearances at Café Society, a nightclub in New York that allowed integrated acts. Here, White performed songs about racial equality to a white audience — something that folk singer Cynthia Gooding noted was a dangerous for White to do (learn more about White’s experiences at the Café Society in Dorothy Siegel’s The Glory Road: The Story of Josh White). The famed ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax once stood up for White when a Café Society patron called him derogatory names and threatened him. Lomax later had White appear on his radio show The Columbia School on Air.

The Roosevelts

In 1940, Lomax got White involved with an event sponsored by Eleanor Roosevelt. The Roosevelts were so taken by White’s music that they invited him back to the White House to perform several more times, often in integrated acts at a time when Washington was still segregated. When White’s protest album, Southern Exposure: An Album of Jim Crow Blues was sent to President Roosevelt in 1941, Roosevelt invited White to give a private performance of all six songs. Afterward, Roosevelt asked about one song in particular, “Uncle Sam Says,” whose lyrics are a straightforward indictment of segregation in the war-time military. It is said that Roosevelt asked White if he, the President, was Uncle Sam in the song. White is said to have answered honestly, yes. The two talked for some time and became close friends, with White and his wife being invited back to the White House for holidays and dinners.

The Blacklist

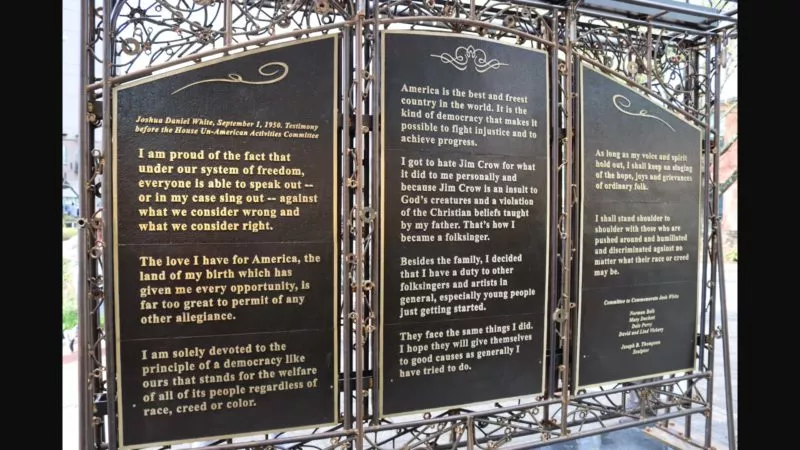

White was touring Europe with Eleanor Roosevelt in 1950 when things began to unravel for him. His activist leanings were well known, and he found himself to be the latest target of the infamous McCarthy era Hollywood Blacklist. He was coerced into testifying before the House Committee on Unamerican Activity. Here, he both asserted his patriotism and disavowed Communism while also spending time decrying the racism of Jim Crow laws and asserting his dedication to the principles of democracy. Democracy, he said, stands for the welfare of all people, regardless of race, color or creed. The press, however, overlooked much of this part of his testimony, and instead emphasized a comment he made about Paul Robeson. Headlines such as “Singer Repudiates Robeson” and “Josh White hits Robeson for Aiding Foes of the U.S.” turned White’s left-leaning fans against him.

White’s career in the United States never fully recovered from these events. He was not removed from the blacklist, despite his testimony, and he lost his contracts, radio show and movie offers. He and his wife relocated to Europe for a time, where he ran a radio show in between tours. They returned stateside in 1954. Upon his arrival home, he was greeted by FBI agents and interrogated. It would be another ten years before he was lifted from the blacklist.

White’s Waning Years

White’s tides finally changed in 1963 when President John F. Kennedy, who was a big fan of folk music, invited White to appear on a CBS-TV special. Later that year, White also performed during the famous March on Washington, which was organized by Martin Luther King Jr., and broadcast on national television.

The years, however, were beginning to take their toll. Chronic malnutrition as a child coupled with the excesses of life on the road left White with multiple maladies, including ulcers, psoriasis and emphysema. He had suffered a heart attack in 1961 and would suffer two more before he passed away during surgery in 1969 when he was only 54-years-old.

In 2021, White was forever memorialized in Greenville with a sculpture honoring his life and work. The free-standing relief sculpture, which is located on the corner of Hammond Street and Falls Park Way, includes excerpts from White’s testimony to from the House Committee on Un-American Activities hearing, attesting to White’s heart and dedication. “I will stand shoulder to shoulder with those who are pushed around and humiliated and discriminated against no matter what their race or creed may be,” the memorial reads.

Learn more about White and hear his tunes in “Who is Josh White?”, a remembrance by the City of Greenville.