Saluda River

Indigenous Water Protectors’ Long Tradition

Long before the first Europeans began settling near the Saluda and Reedy Rivers in what is now known as Greenville County, Indigenous people of the Catawba and Cherokee nations farmed and hunted along the river banks. The Catawba, whose name means “people of the river” inhabited large swaths of territory throughout North and South Carolina and Virginia, where they fished, hunted, and planted crops. The Cherokee had 27 known villages established in the Upstate, where the rivers — the same rivers that feed into Greenville’s drinking water sources today — provided sustenance and a way of life.

Little remains today of the Cherokee and Catawba communities in Greenville County. People who identify as Cherokee are dwindling, and the only federally recognized reservation in South Carolina is the 700-acre Catawba reservation in Rock Hill. However, the traditional reciprocal relationship with rivers and other waterways remains a way of life for many.

Juanita Wilson, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), told Facing South that her great-grandparents taught her that rivers are living, breathing entities, and it is the duty of the people to protect their wellbeing. Today, Wilson partners with other Native communities and with non-Indigenous allies to help “Long Man,” a traditional name for rivers, continue to breathe. This October, Wilson spearheaded the second annual “Honoring Long Man Day” in Cherokee, NC., where she and others organized river clean-up events. The aim of the event is not just to spend one day cleaning up a river. Rather, Wilson and her partners say that the aim is to educate and encourage a “cultural awakening or reawakening” that inspires us all to commit to water stewardship.

This Native American Heritage Month, MetroConnects would like to take a moment to acknowledge Indigenous peoples’ long tradition of land and water stewardship and to commit to joining them in protecting our most precious natural resources.

A Brief History of Indigenous Nations of the Upstate

As many in Greenville prepare to gather with family, friends, and neighbors for the Thanksgiving holiday, MetroConnects would like to take a moment to acknowledge the land that Greenville County now occupies, which is the traditional land of the Cherokee people, and is where the Catawba and other Indigenous people found food and sustenance.

The Cherokee Nation

The first human inhabitants of what is now known as Greenville County were likely part of the Cherokee Nation, which was the largest single Native American Nation in the south. Historians hypothesize that the Cherokee, who are descendants of Iroquoian-speaking peoples, migrated from the northeast, following big game like buffalo and caribou. As these large animals became extinct, the Cherokee began hunting small game and relying more heavily on vegetables and grain for sustenance. Without the need to follow the migratory patterns of large game, the Cherokee began settling in villages on both sides of the Appalachian mountains, as far south as South Carolina and Georgia.

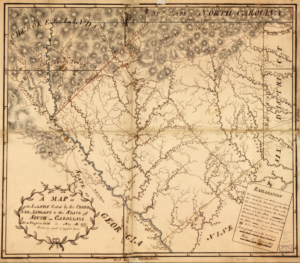

Historians have found evidence of 27 Cherokee villages in northwest South Carolina, including in what is now Greenville County, Pickens County, and Oconee County, the latter of which is the Cherokee word for “beside the water.” These villages, which consisted of 50 to 100 houses, were situated along the Saluda and Reedy Rivers, among other bodies of water, where the inhabitants fished, hunted, and planted “three sisters” crops of corn, beans, and squash.

Cherokee are a matrilineal society that governs through democratic consensus as well as the leadership of priests and chiefs. Familial ties and clan affiliations come through Cherokee women, who traditionally own the houses and fields and pass them on to their daughters.

The Cherokee first encountered European colonists in 1540, but sustained relationships between the Cherokee and colonists did not establish until the early to mid-18th century when Cherokee allied with England. By the 1760s, after the Cherokee and colonists both suffered extensive losses in the Cherokee War, smallpox hit for the second time. Since Native Americans did not have the immunity built up to protect against the disease, the populations of Indigenous nations plummeted. Under pressure from colonists, Cherokee submitted to a series of so-called “voluntary” land cessions between 1768 and 1775, ultimately ending in the loss of 50,000 square miles of Cherokee land.

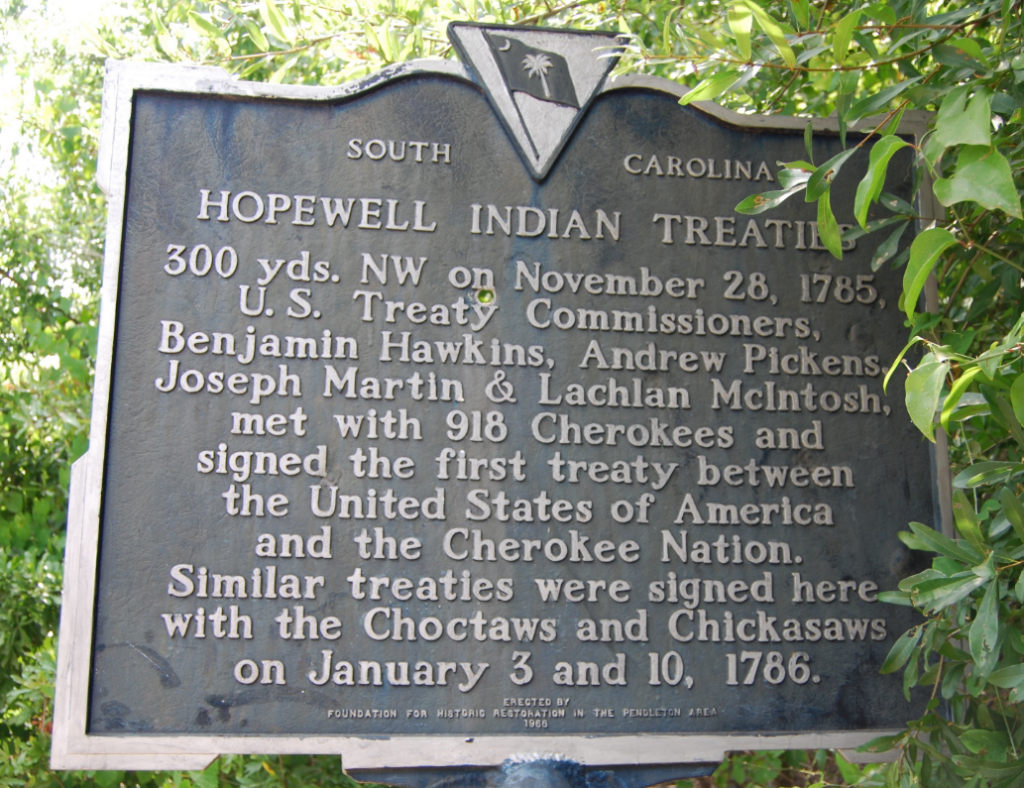

The loss of land continued into the Revolutionary War period when the Cherokee sided with the British. A brutal multi-colony army attack on Cherokee towns and food stores in 1776 caused mass devastation to Cherokee Villages. Particularly violent were the attacks carried out in villages located in what was known as the “Lower Towns” in present-day South Carolina. By 1777, the Cherokee had ceded most of their Lower Town land. In 1785, the Cherokee signed the Treaty of Hopewell near present-day Seneca and on March 22, 1816, ceded their last strip of land in South Carolina. An assimilation campaign began in South Carolina around this time, contributing to cultural genocide. Today, there is no federally recognized Cherokee nation in South Carolina, although many residents in the Upstate do claim Cherokee descent. The Museum of the Cherokee in Walhalla has an extensive collection of Cherokee artifacts dating back tens of thousands of years.

The Catawba Nation

The Catawba, who called themselves “people of the river,” were likely in the area beginning around the same time the Cherokee arrived, also having migrated south. They are descendants of people who spoke a Siouan language and inhabited most of the Piedmont area of North and South Carolina and parts of Virginia. Their largest territory was in the Catawba River Valley straddling the present-day North Carolina-South Carolina border. Early colonial estimates show that the Catawba population was around 15,000 to 25,000 people when European settlers arrived in the early 16th century. By the time colonists settled in the Piedmont area in the 1750s, that population was less than 1,000 people, many having been decimated by genocide, war, and smallpox.

In 1763 the Catawbas received title to 144,000 acres from the King of England, but it was difficult to protect the land from colonists who were settling in the area. Many began renting to the colonists, who then put pressure on South Carolina to negotiate with the Nation so that they could own the land outright. To avoid being forced west on what is known as the Trail of Tears, the Catawbas agreed to a treaty in which they were forced to relinquish their 144,000 acres in exchange for a 700-acre parcel near present-day Rock Hill. That area remains Catawba territory today, and the Nation won Federal recognition in 1993 following a hard-fought, 20-year court battle. The Catawba are now the only Federally recognized Nation located in the state of South Carolina.

The Westo and Shawnee/Savannah

The Westo, also spelled Westoe, were of the Yuchi language family. They were driven south by the Iraqois, and moved through Virginia to the Carolinas and Georgia, where they traded along the Savannah River. They were known as fierce warriors, and had a distinct advantage over other tribal nations because they obtained guns from colonists in Virginia. However, their military prowess was eventually seen as a threat by colonists, who then paid other area Nations, notably the Savannah of the Shawnee language group, to drive off the Westo. The Westo were eventually decimated, and no surviving members are recorded past 1680, although many likely integrated into other Nations in the area.

The Savannah were a band of the Shawnee, which means “southerners.” Some historians argue that a variant of the name Savannah is Chaouanons, which has etymological connections to French. The Shawnee were a divided and migratory nation, but the band that settled along the Savannah before 1680 are known in the history books for having driven off the Westo. By the 18th century, the Shawnee appear to have begun moving back north to present-day Pennsylvania, with no written record of Shawnee in South Carolina after 1731.

Sign up for our newsletter to keep up on the latest with MetroConnects.